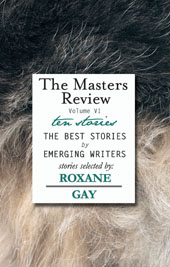

Matthew Sullivan, “Little Men” (The Masters Review Anthology, Volume VI)

Another solid story in The Masters Review Anthology, Volume VI (2017), is “Little Men,” by Matthew Sullivan.

Lois is at her son’s baseball practice one day when a little

man (“Three, four inches” tall [p. 63]) lands on her sandal. She takes in the

little man and keeps him fed and cared after in a tin box or a shoebox for some

time, while we witness the harshness of her day-to-day life: her son, Alan, is

a criminal in the making, who crushed a fellow player’s mouth with a bat in

practice and who enjoys torturing animals and toys. Lois gets visions of him in

the future, committing crimes. Her husband, Howard, claims he’s traveling for

work while he’s on week-long escapades with prostitutes. She sticks with Howard

into old age, and in the dramatic present of the story, forty years after Lois

found the little man, we see Howard forgetful and oxygen-dependent, looked

after by his wife.

Lois is having serious issues remembering things, so the

many flashbacks and memories laced into the story come naturally to a piece

textured by Lois’s struggle to remember. We learn that Alan did in fact become

a criminal: he violently murdered his wife.

Howard and Lois expect Alan for dinner the day the story

unfolds, but we find out that he is in jail and will be executed the following

day. Someone from church comes to ask Lois to pick up the phone that night, to

receive Alan’s last phone call. The phone rings at the end of the story, and

neither Howard nor Lois pick up.

I have omitted the fate of the little man: at one point, Lois

is ironing Howard’s shirts with the little man close by her. Lois is bothered

by the little man’s constant crying, and furious at Howard’s infidelity and her

son’s behavior. The little man tells her, sobbing, that what he wants is her.

She envisions a life with the little man, away from it all. “And then Lois

brought the iron down right on top of him, the Little Man, pinning him against

the edge of the ironing board, and pressed, pressed, pressed—first with her

arm, then with the full weight of her body, rocking the iron bow to stern until

his squealing became hissing and the hissing bubbled to a stop” (p. 70). With

this scene, we find out how the little man ended up dead. Lois had found him dead

and burnt early in the story and for several pages puzzled over what happened.

The substory with the little man is, of course, very suggestive.

The author plays with the idea of the Fall from our first glimpses of the

little man: “Not five minutes before the Little Man’s fall […]” (p. 55); “the

Little Man had not fallen, but jumped” (p. 56). Lois’s struggle with the men in

her life is bound up with the little man, with his burning desire for her and

her ability to control and destroy him. The title invites us to make this

connection: the story is not called “Little Man,” but “Little Men.” They all

depend on her and drain her and use her.

My main objection with the story, if I have any, is that it

starts on very firm footing compared with the swaying quality of the rest of

the narrative: we get a clear look at the little man and how he entered Lois’s

life. It makes for a good start to the story, but the rest of the time we’re

hamstrung by Lois’s faulty memory, so why start with such clarity? It would’ve

been truer to the story, though perhaps dramatically less attractive, to begin

with her finding the corpse of the little man and walk us through Lois piecing

together her memories of the little man afterward. Finding out about Alan’s

execution as we did speaks well of the story and is true to the framework of

Lois’s memory.

Comments

Post a Comment